After Last Season (2009)

“My uncle saw a coyote by that tree over there. It stood there for several seconds and then went away.”

Suspension of disbelief (in Coleridge’s words, “poetic faith”) is easier than it sounds, for we love narratives and will gladly, if smugly, accept all kind of glitches if only the basic story promises to hold our interest. Pointing out the goofs in a Spielberg movie may be good fun, but who cares for the laws of physics when it’s all so much fun?

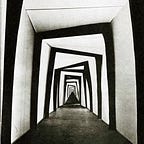

And then there is After Last Season. A brave, but tragic little film, asking “Where am I?”, as if some horrible accident had left it stranded on this planet with no way to phone home. A film genuinely unable to depict a regular office building: Shot in an unheated building under construction, it attempts to cover up debris and chaos with digitally imposed white walls. Clumsy noise reduction results in what sounds like flushing toilets cluttering the soundtrack. Occasionally, there are cuts to wall signs, no, to rough print-outs affixed with adhesive tape. Potemkin would have died laughing.

The official plot synopsis speaks of the protagonists having to re-evaluate their lives; however, the film implies that they have no chance in this fragmentary, ever-threatening world where one character’s desire for the “access code” leads to him being imprisoned in something which is not even a prison. (How can the void imagine a void on top of itself?)

The director, going by the pseudonym of “Mark Region”, aimed to produce a mystery thriller, citing Hitchcock as a model. But the film’s utter lack of technical competence in regards to acting, script, sound, editing, camerawork (amazingly, it was shot on 35 mm) and set decoration makes Birdemic look like Citizen Kane. The silent lament of a lost soul wafts through the film like the vague music fragments which drift in and out at random times. Maybe it’s all a dream? That would be a comfort, wouldn’t it?

When other “cult” directors create their own world of clichés and private idiosyncrasies, however weird and disturbing they may be to outsiders, they are in themselves coherent and stable (after all, the auteur lives in them). But Region can do little more than build a makeshift house of cards in which nothing is self-evident and where seemingly everyday things (such as the social phenomenon called “communication”) need to established as carefully as the concepts of quantum physics. It is an autistic world in which the characters are valiantly trying to simulate life as the norms perform it:

“Did he love the town?”

“Sometimes, he gave me the impression that he didn’t, but my grandfather stayed in Ringham most of his life.”

“What did he do in Ringham?”

“He became a carpenter.”

[Mutual laughter.]

“My father also grew up in a small town. He stayed in this town until he was 16. Later on, his family moved away to the suburbs of a large city.”

[Pause.]

“Wow, you’ve got a nice radio clock!”

Whereupon the film cuts to what is literally a radio with a clock placed in front of it. Is this a Zen koan? An absurdist joke? Or is it the best the filmmakers could come up with when asked to provide a radio clock? We may never know. The unfathomable “Wholly Other” is not Karl Barth’s God, but Mark Region’s film.